Композитор Владимир Раннев трактует рассказ Мамлеева «Жених» и фрагменты повести Чехова «Степь» как этапы развития одного сюжета. Первый – образец «жестокой» прозы, второй – созерцательный и почти бессобытийный.

Написанный в 1980 году, рассказ Мамлеева представляет собой гиперреалистическое и одновременно фантасмагорическое исследование одного «случая», произошедшего в простой городской семье и радикально поменявшего жизнь героев. Герой чеховской «Степи», мальчик Егорушка, едет в город на воспитание к дальним родственникам, радуясь миру природы, но уже готовясь к открытию нового, непознанного и страшного мира – мира людей.

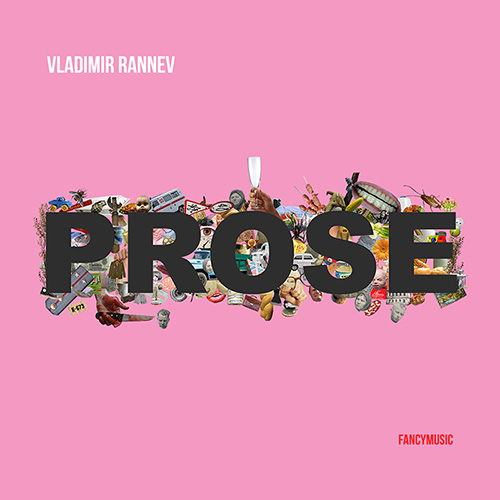

Перед нами – один человек, но увиденный в разное время своей жизни, как если бы Чехов и Мамлеев писали об одной, общей на всех, жизни, и общем мороке. Разные типы текстов и повествований создают напряжение между ними и диктуют принципиальную разность их подачи, что становится основой драматургии оперы и помогает развернуть перед зрителем высказывание о сложной природе взаимоотношений людей в современном обществе. По задумке композитора (он же – режиссер премьерной постановки в Электротеатре Станиславский), оба текста разворачиваются в опере одновременно: повесть Чехова пропевается, в то время как рассказ Мамлеева подается визуально, в виде огромного комикса. При этом певцы, выступая в этом комиксе героями Мамлеева, поют текст Чехова. Таким образом, музыка «Прозы» – лишь одна из составляющих драматургического целого. Но даже вне театрального действия она остается самостоятельным музыкальным произведением.

Кристина Матвиенко, театральный критик

Composer Vladimir Rannev interprets Yury Mamleev’s story “The Bridegroom” (1980), and fragments of Chekhov’s story “The Steppe” (1888) as different stages in the development of a single story. The former is an example of “cruel” prose, the latter is meditative and virtually event-free.

Mamleev’s story is simultaneously the hyper-realistic and phantasmagorical exploration of an incident that occurs in a common Russian family, changing it radically and incontrovertibly. The boy Yegorushka, the hero of Chekhov’s “The Steppe,” is traveling to be raised by distant relatives. He is thrilled by the natural world surrounding him, but is already preparing for the discovery of a new, alien and terrifying world – the world of people.

We see before us a single person, captured at di erent moments in his life, as if Chekhov and Mamleev had written about one and the same life, and the very same anxieties. The di erent types of texts give rise to a tension that dictates a principal di erence in the way they are presented. In turn, this gives rise to the dramaturgical nature of the opera, and helps reveal to the viewer a statement about the complex nature of the relationships among people in contemporary society. According to the idea of the composer (who is also the director of premiere production at the Stanislavsky Electrotheatre), both texts unfold in the opera simultaneously: Chekhov’s story is sung, while Mamleev’s story is presented visually, in the form of a huge comic book. At the same time singers, performing roles of Mamleev’s characters in this comic book, sing the text of Chekhov. Thus, music of “Prose” is only one of the constituent dramatic whole. But even outside the theater, it remains an independent musical work.

Christine Matvienko, theatrical critic